Guillain-Barre syndrome

GBS; Landry-Guillain-Barre syndrome; Acute idiopathic polyneuritis; Infectious polyneuritis; Acute inflammatory polyneuropathy; Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy; Ascending paralysis; Guillain-Barré syndrome

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a serious health problem that occurs when the body's defense (immune) system mistakenly attacks part of the peripheral nervous system. This leads to nerve inflammation that causes muscle weakness or paralysis and other symptoms.

Causes

The exact cause of GBS is unknown. It is thought that GBS is an autoimmune disorder. With an autoimmune disorder, the body's immune system attacks itself by mistake. The incidence of GBS increases with increasing age, but can occur at any age. It is most common in people between ages 30 and 50.

GBS may occur with infections from viruses or bacteria, such as:

- Influenza

- Some gastrointestinal illnesses

- Mycoplasma pneumonia

- HIV, the virus that causes HIV/AIDS (very rare)

- Herpes simplex

- Mononucleosis

- COVID-19

GBS may also occur with other medical conditions, such as:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Hodgkin disease

- After surgery

GBS damages parts of nerves. This nerve damage causes tingling, muscle weakness, loss of balance, and paralysis. GBS most often affects the nerve covering (myelin sheath). This damage is called demyelination. It causes nerve signals to move more slowly. Damage to other parts of the nerve can cause the nerve to stop working.

Symptoms

Symptoms of GBS can get worse quickly. It may take only a few hours for the most severe symptoms to appear. But weakness that increases over several days is also common.

Muscle weakness or loss of muscle function (paralysis) affects both sides of the body. In most cases, the muscle weakness starts in the legs and spreads to the arms. This is called ascending paralysis.

If the inflammation affects the nerves of the chest and diaphragm (the large muscle under your lungs that helps you breathe) and those muscles are weak, you may need breathing assistance.

Other typical signs and symptoms of GBS include:

- Loss of tendon reflexes in the arms and legs

- Tingling or numbness (mild loss of sensation)

- Muscle tenderness or pain (may be a cramp-like pain)

- Uncoordinated movement (cannot walk without help)

- Low blood pressure or poor blood pressure control

- Abnormal heart rate

Other symptoms may include:

- Blurred vision and double vision

- Clumsiness and falling

- Difficulty moving face muscles

- Muscle contractions

- Feeling the heart beat (palpitations)

Emergency symptoms (seek medical help right away):

- Breathing temporarily stops

- Cannot take a deep breath

- Difficulty breathing

- Difficulty swallowing

- Drooling

- Fainting

- Feeling light headed when standing

Exams and Tests

A history of increasing muscle weakness and paralysis may be a sign of GBS, especially if there was a recent illness.

A medical exam may show muscle weakness. There may also be problems with blood pressure and heart rate. These are functions that are controlled automatically by the nervous system. The exam may also show that reflexes such as the ankle or knee jerk are decreased or missing.

There may be signs of decreased breathing caused by paralysis of the breathing muscles.

The following tests may be done:

- Cerebrospinal fluid sample (spinal tap)

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) to check the electrical activity in the heart

- Electromyography (EMG) to test the electrical activity in muscles

- Nerve conduction velocity test to test how fast electrical signals move through a nerve

- Pulmonary function tests to measure breathing and how well the lungs are functioning

Treatment

There is no cure for GBS. Treatment is aimed at reducing symptoms, treating complications, and speeding up recovery.

In the early stages of the illness, a treatment called apheresis or plasmapheresis may be given. It involves removing or blocking the proteins, called antibodies, which attack the nerve cells. Another treatment is intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg). Both treatments lead to faster improvement, and both are equally effective. But there is no advantage to using both treatments at the same time. Other treatments help reduce inflammation.

When symptoms are severe, treatment in the hospital will be needed. Breathing support will likely be given.

Other treatments in the hospital focus on preventing complications. These may include:

- Blood thinners to prevent blood clots

- Breathing support or a breathing tube and ventilator, if the diaphragm is weak

- Pain medicines or other medicines to treat pain

- Proper body positioning or a feeding tube to prevent choking during feeding, if the muscles used for swallowing are weak

- Physical therapy to help keep joints and muscles healthy

Support Groups

These resources may provide more information about GBS:

- Guillain-Barré Syndrome Foundation International -- www.gbs-cidp.org

- National Organization for Rare Disorders -- rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/guillain-barre-syndrome

Outlook (Prognosis)

Recovery can take weeks, months, or years. Most people survive and recover completely. In some people, mild weakness may persist. The outcome is likely to be good when the symptoms go away soon after they first started.

Possible Complications

Possible complications of GBS include:

- Breathing difficulty (respiratory failure)

- Shortening of tissues in the joints (contractures) or other deformities

- Blood clots (deep vein thrombosis) that form when the person with GBS is inactive or has to stay in bed

- Increased risk of infections

- Low or unstable blood pressure

- Paralysis that is permanent

- Pneumonia

- Skin damage (ulcers)

- Breathing food or fluids into the lungs

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Seek medical help right away if you have any of these symptoms:

- Trouble taking a deep breath

- Decreased feeling (sensation)

- Difficulty breathing

- Difficulty swallowing

- Fainting

- Loss of strength in the legs that gets worse over time

References

Chang CWJ. Myasthenia gravis and Guillain-Barré syndrome. In: Parrillo JE, Dellinger RP, eds. Critical Care Medicine: Principles of Diagnosis and Management in the Adult. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 61.

Katirji B. Disorders of peripheral nerves. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 106.

Sejvar JJ, Baughman AL, Wise M, Morgan OW. Population incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36(2):123-133. PMID: 21422765 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21422765/.

Trujillo Gittermann LM, Valenzuela Feris SN, von Oetinger Giacoman A. Relation between COVID-19 and Guillain-Barré syndrome in adults. Systematic review. Neurologia (Engl Ed). 2020;35(9):646-654. PMID: 32896460 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32896460/.

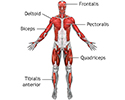

Superficial anterior muscles - illustration

Superficial anterior muscles

illustration

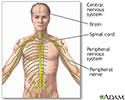

Brain and nervous system - illustration

Brain and nervous system

illustration

Central nervous system and peripheral nervous system - illustration

Central nervous system and peripheral nervous system

illustration

Motor nerves - illustration

Motor nerves

illustration

Superficial anterior muscles - illustration

Superficial anterior muscles

illustration

Brain and nervous system - illustration

Brain and nervous system

illustration

Central nervous system and peripheral nervous system - illustration

Central nervous system and peripheral nervous system

illustration

Motor nerves - illustration

Motor nerves

illustration

Review Date: 5/4/2021

Reviewed By: Joseph V. Campellone, MD, Department of Neurology, Cooper Medical School at Rowan University, Camden, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.